This essay continues my series of monthly posts in which I select one ‘climate’ book to highlight and review from one of the 44 years of my professional career in climate research (starting with 1984, my first year of academic employment). The series will end in September 2027, the month in which I shall retire. See here for more information about the rational for this series, and the criteria I have used in selecting my highlighted books.

This ‘2002 essay’ can be download as a pdf.

In mid-July 1995 a severe heat wave affected parts of the American mid-West, centred on the state of Illinois and the city of Chicago. On the morning of Wednesday 12th July, the Chicago Sun-Times ran a headline on one of its news pages, ‘Heat Wave On The Way—And It Can Be A Killer’. The heat wave peaked between the 12th and 15th July, with a maximum daytime temperature of just over 41°C being reached on Thursday 13th. High humidities, the exacerbating effects of the urban heat island, and the still air of the stationary anticyclone meant that for two consecutive nights the temperature in the city never fell much below 30°C. It was later estimated that the “excess” death toll of the heat wave was over 700, most of the deaths occurring between the 14th and 17th July, lagging the maximum temperatures by 48 hours. For a couple of days the city’s morgues struggled to cope with the number of bodies.

So, what is it that makes a heat wave “A Killer”, as the Chicago Times claimed, even before the heat began? What caused 700 people to die over this long, hot weekend in mid-July? Was it the extreme temperatures, and were these temperatures caused by a change in the climate resulting from historic emissions of greenhouse gases? Or should the blame be placed on local non-meteorological factors linked to, for example, early warning systems, architectural design, urban planning, emergency responders, or other sociological and cultural features of the city? In other words, was the disaster natural or human-caused and, if human-caused, was it due to the build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere or to the nature of Chicago’s social, economic and political systems?

These questions about climate and ‘blame’ are highly pertinent today. Over the past decade, there has been a growing number of climate litigation cases brought before national or international courts. These cases use judicial processes to sue coal, oil and gas companies for climate-related deaths, morbidity or economic damage “caused” by carbon dioxide emissions emanating from these companies’ products. But back in 1995, long before climate litigation was a thing, these were the exact same questions that a young American sociologist named Eric Klinenberg was also asking.

A few months after the heat wave, Klinenberg, aged 24, returned to his home city of Chicago from California, where he had just started a graduate PhD programme in the Faculty of Sociology at the University of California at Berkeley. He was puzzled by the recollections of the 1995 summer heat wave among his fellow Chicagoans. Although they had lived through the heat, and had absorbed the magnitude of the disaster, they seemed to have blocked out its significance and implications from their memory. Wanting to dig deeper into the reasons why this might be so, Klinenberg decided to make this heat wave the subject of his PhD dissertation. The results of this research—his PhD was awarded in 2000—led directly to the publication of his book, ‘Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago’, which I have selected as my 2002 Climate Book of the Year.

‘Heat Wave’ provided the first really penetrating and rigorous empirical analysis of how heat kills people. It is grounded in 16 months of fieldwork Klinenberg undertook in Chicago, paying careful attention to the political sociology of the city. During this time, he observed and listened to people’s stories, gathering some of their life histories, he read police and first responder reports, he examined documentation in the Public Administration Office and in the Medical Examiners’ Office, and interviewed journalists and public health officials.

Klinenberg’s book extended existing understanding of precisely how a suite of extreme meteorological phenomena—droughts, floods, storms, hurricanes, blizzards and, now, heat waves—create disasters. This happens because of the differentiated exposure and vulnerability of people at risk, as much as it does by the direct physicality of the atmosphere’s behaviour. In this respect, his study complimented others which had done something similar for droughts[1] and those which later would do so for hurricanes.[2] ‘Heat Wave’ therefore provides an analysis—what Klinenberg calls ‘a social autopsy’—of this weather-initiated disaster, and the ensuing deaths it caused. Paradoxically, he accomplishes this without studying the weather itself. He achieves his objective of explaining how heat kills without any analysis of climatological and meteorological data, and without any explanations of what caused the exceptional heat wave.[3] For example, the book’s index contains no entry for ‘climate’, ‘climate change’, ‘global warming’ or ‘the climate crisis’. This is a book written by a sociologist, not a climatologist, and yet it is of profound importance for our understanding of climate change and its relationship with the human world. It is a story of a weather-initiated disaster, but told from the inside out. It discloses the social, cultural and political processes at work, not the meteorological ones.

On publication, the University of Chicago Press conducted an interview with Klinenberg and asked him, “Would you call the heat wave deaths primarily a social disaster, rather than a natural one?” His reply was clear,

“Of course forces of nature played a major role. But these deaths were not an act of God. The authors of an article in the American Journal of Public Health said that the most sophisticated climate models ‘failed to detect relationships between the weather and mortality that would explain what happened in July 1995 in Chicago.’ Hundreds of Chicago residents died alone, behind locked doors and sealed windows, out of contact with friends, family, and neighbours, unassisted by public agencies or community groups. There’s nothing natural about that.“

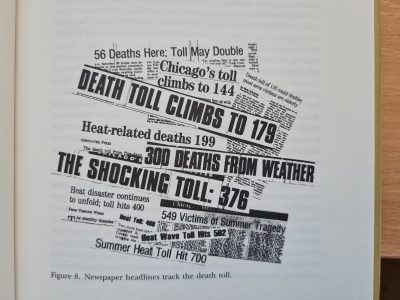

Klinenberg argues that the heat wave should be understood as a major cultural event, as well as a public health crisis. Yet, perplexed, he also observes that “for much of the nation it never registered as a major happening, and its legacy is difficult to trace.” [p.23] As social worker William Sites noted in his review of the book, “The heat wave never became more than a spectacular weather story … even local newspapers that routinely focus on stories of race, poverty and injustice failed to cover the crisis effectively because they, too, viewed it as just another natural disaster.”[4] [See image here, Figure 8 from Klinenberg’s book].

‘Heat Wave’ received effusive praise from senior academics in urban studies and in political sociology and was widely reviewed in journals across the social science and humanities. Thus sociologist Richard Sennett blurbed the book as “meticulously documented and beautifully written, the book is both a pathbreaking contribution to urban studies and powerful account of social breakdowns in American life”, and Nobel Prize winning welfare economist Amartya Sen saw likewise: “By analysing the social and political causes of so-called heat deaths, [he] has powerfully illuminated the causation and culpability associated with the terrible events in Chicago”. Karen Tomis, writing for the Journal of the American Medical Association, recommended that “…the first part of the book should be required reading for public health students and practitioners alike.”[5]

As well as receiving praise, Klinenberg had to defend his analysis from some powerful critics. One such was John Wilhelm, the commissioner of the Chicago Department of Public Health, who in his review of the book criticised the reliability of the eye-witness accounts Klinenberg used and was also sceptical of the racial disparities of death rates which his statistical analysis revealed. Klinenberg felt it necessary to defend himself against both charges and reiterated his view that “my social autopsy shows that an emerging population of poor, old and isolated urban residents makes extreme summer weather especially dangerous. Wilhelm [in fact] agrees.”[6]

‘Heat Wave’ won several scholarly prizes, including the American Sociological Association Robert Park Book Award, the Urban Affairs Association best book award, the British Sociological Association book prize, and the Mirra Komarovsky Book Prize. It also generated wider public exposure, first through a theatrical adaptation of the book, premiered in Chicago in 2008. And then, in 2018, filmmaker Judith Hefland produced ‘Cooked: Survival by Zip Code’, a documentary which explored the unequal death rates Klinenberg had noted across Chicago during the 1995 heat wave.

In August 2003, the year following publication of ‘Heat Wave’, western Europe also experienced a severe heat wave, with excess deaths estimated across the region at between 30,000 and 50,000. The city of Paris was particular badly affected and many of the Parisian victims had exactly the same social profile that Klinenberg had identified in Chicago: elders living alone, in poor neighbourhoods, and with weak social networks. As with Chicago after 1995, the aftermath of the 2003 European heat wave led to the design and implementation of national heat wave management plans in several affected countries. These paid careful attention to the sociological and public health interventions which could ameliorate for specific groups of vulnerable people the extreme temperatures and humidities of a heat wave.

I purchased and read Klinenberg’s book in 2009, seven years after it was first published, and I remember it offered a powerful defence of the argument that the consequences of weather extremes are always conditioned on the state of the society which experiences them. I applied this argument to my own analysis of a heat wave which had occurred in 1900 in the east of England. Taking my cue from Klinenberg, who showed that it was “… the very particular ethnic, cultural, architectural and political characteristics of Chicago [that] give the July 1995 heatwave its shape, significance and meaning”, I emphasised in my own work that these characteristics “cannot be discerned through a reading of the thermometers. The meaning of a climate extreme is inextricable from the culture which it encounters.”[7]

One frequently hears the claim that climate change has led—or will lead—to this or that number of people being killed. But whether a change in the climate kills people, and which people it kills, always depends on non-climatological factors. Extreme weather kills as much because of sociology as because of physiology. Attributing deaths and morbidities to either climate (natural) or climate change (human influenced) can easily distract from what matters more.

Meteorological extremes—whether floods, snowstorms, tidal surges, hurricanes or heat waves—do not operate in isolation from the social conditions and capacities of the people they affect. This has now become an axiom in public health planning, but is one too easily forgotten in some of the causal rhetoric around climate change. As Klinenberg observed in the case of Chicago, while the dramatic spectacle of the meteorological extreme event is unmissable, the less visible social, cultural, economic, and organisational characteristics which determine whether the event will lead to excess deaths is often missed.

Klinenberg was later to be appointed Professor of Sociology at New York University, where today he is Helen Gould Shepard Professor of Social Science and Director of the Institute for Public Knowledge in New York. ‘Heat Wave’ remains his best known book and has received over 3,000 citations in the scholarly literature, putting it in the ‘highly-cited’ category for an academic book. Even now, these citations continue to increase almost year-on-year—2021 and 2024 were the two years with the highest citations—demonstrating the book’s enduring insights into how heat kills.

The enduring importance of ‘Heat Wave’ was also evidenced by the publication of a second edition in 2015, for which Klinenberg wrote a new Preface. He pointed out how, 20 years after the Chicago event, climate change was making extreme weather events in urban centres a major challenge for cities. To meet this challenge, he wrote, requires more than just relief or humanitarian responses, it requires adaptation planning, a commitment to climate-proofing infrastructure, and heat wave management plans. And as Klinenberg had written 13 years earlier,

“We know that more heat waves are coming. Every major report on global warming … warns that an increase in severe heat waves is likely. The only way to prevent another heat disaster is to address the isolation, poverty, and fear that are prevalent in so many American cities today. Until we do, natural forces that are out of our control will continue to be uncontrollably dangerous.“

© Mike Hulme, July 2025

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Other significant book published in 2002

Athanasiou,T. and Baer,P. (2002) Dead Heat: Global Justice and Global Warming. New York: Seven Stories Press. 176pp.

To my knowledge, no full length book in the English language was published in the twentieth century that dealt with the specific relationship between justice and climate change. This is not to say that concerns about justice were not present earlier in the writing, politics, public discourse and advocacy around climate change. But it wasn’t until 2002, when climate activists Tom Athanasiou and the late Paul Baer (1962-2016) published Dead Heat: Global Justice and Global Warming, that this connection was explicitly foregrounded in a book’s title, cover and content. ‘Dead Heat’ is a short, sharp intervention—about 25,000 words long—which pulled no punches and which confronted the problem head-on. The book is written in a direct and bold manner with little room for nuance. In their words, “the battle against global warming is key to the larger battle for global justice … its outcome may, in fact, be almost as decisive politically as it will be ecologically” (p.9).

The book’s proposition builds upon the idea of Contraction-and-Convergence, originating with Global Commons Institute in 1990. This was a proposed global framework for reducing greenhouse gas emissions equitably, in which the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases would be reduced to a “safe” level (‘contraction’), but achieved by every country bringing its emissions-per-capita to a level which would be equal for all countries (‘convergence’). In ‘Dead Heat’, Athanasiou and Baer re-frame this idea as ‘eco-equity’, the name of the campaigning NGO which they founded in 2002 shortly after the USA withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol. ‘Eco-equity’ then mutated into Greenhouse Development Rights (GDR), an international framework in which the obligations assigned to nations would be based on a combination of responsibility (their contribution to the problem) and capacity (their ability to pay). A key feature of the GDR framework is that it assigns a ‘right to development’ to individuals, such that individuals with incomes below a ‘development threshold’ are nominally exempted from obligations to pay for mitigation and adaptation.

Athanasiou and Baer dedicate ‘Dead Heat’ to the pioneering Indian environmentalist Anil Agarwal (1947-2002), who died the year the book was published and who, along with his colleague Sunita Narain, had first drawn attention to the idea of environmental colonialism, from which they drew their inspiration.

[1] For example: Sen,A. (1981) Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation Hardcover. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 224pp; Garcia,R.V. (1981) Nature Pleads Not Guilty: The 1972 Case History (Drought and Man). London: Pergamon.

[2] For example: Brunsma,D.L., Overfelt,D. and Picou,J.S. (eds.) (2008) The Sociology of Katrina: Perspectives on a Modern Catastrophe. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

[3] For a climatological investigation of the heat wave, see: Karl,T.R. and Knight,R.W. (1997) The 1995 Chicago heat wave: how likely is a recurrence? Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 78: 1107-1120. Asking whether the Chicago heat was “merely an extreme anomaly or part of an ongoing trend toward more extreme heat waves”, these climatologists concluded that “it is unlikely that the macroscale climate of heat waves in the Midwest or in Chicago is changing in any significant manner”.

[4] Sites,W. (2002) Review of ‘Klinenberg,E. (2002) Heatwave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago. University of Chicago Press.’ Social Service Review. 77(4): 619-622.

[5] Tomic,K.E.S (2003) Review of ‘Klinenberg,E. (2002) Heatwave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago. University of Chicago Press.’ Journal of the American Medical Association. 289(12): 1573-1574.

[6] Wilhelm,J. (2002) Review of ‘Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago’. New England Journal of Medicine. 347: 1046; and Klinenberg,E. (2003) Review of ‘Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago’. New England Journal of Medicine. 348(7): 666-667.

[7] Hulme,M. (2012) ‘Telling a different tale’: literary, historical and meteorological reading of a Norfolk heatwave. Climatic Change. 113(1): 5-21.