Shearman,D. and Smith,J.W. (2007) The Climate Change Challenge and the Failure of Democracy. Westport, CT: Praeger. 180pp.

This essay continues my series of monthly posts in which I select one ‘climate’ book to highlight and review from one of the 44 years of my professional career in climate research (starting with 1984, my first year of academic employment). The series will end in September 2027, the month in which I shall retire. See here for more information about the rational for this series, and the criteria I have used in selecting my highlighted books.

This ‘2007 essay’ can be download as a pdf.

The few years either side of 2007 were a period of ‘suspended hope’ regarding the ability of the world to reign-in the worst excesses of human-caused climate change. In that year the IPCC published its Fourth Assessment Report (AR4), exactly halfway between the coming into force of the Kyoto Protocol—in February 2005, achieved with Russia’s ratification of the Protocol—and the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COPs) to the UN Climate Convention, held in Copenhagen in December 2009. IPCC’s AR4 noted the continuing, indeed accelerating emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere—emissions of all greenhouse gases were rising in the 2000s at twice the rate of the 1990s—and at the same time affirmed the much stronger scientific evidence about the reality of human influence on the climate system. The UN Panel’s Report concluded that warming of the climate system was “unequivocal” and it judged that most of this warming since the mid-20th century was “very likely due to the observed increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations”.

So, on the one hand there was the lingering hope that international negotiations could deliver specific treaties, protocols or agreements that would ‘bend the curve’ of emissions—a hope embodied in the recently ratified Kyoto Protocol and a hope anticipated through a future tightening of this Protocol to be negotiated at COP15 in Copenhagen. On the other hand, the empirical evidence of such an achievement was lacking. Fuelled by China’s astonishing economic growth in the 2000s—China’s GHG emissions were growing at 7 percent per annum during this decade—most indicators seemed to be going in the opposite direction.

And so it was around this time in the mid-2000s that some western commentators, public intellectuals and scholars began to ask the troubling question: is the democratic state fit for tackling the problems of climate change? Are the decisions, regulations and policies that may be necessary to arrest climate change ones that open, free, quarrelsome, deliberative and parliamentary democracies are able to make and adhere to?

The first full-length book treatment in the English language of these questions was published in 2002, ‘Democracy and Global Warming’, written by Barry Holden a UK political scientist.[1] Holden started by outlining the view, held he said by many, that “global warming is a matter for scientific experts rather than ordinary people”, that “only authoritarian action can disregard or overcome the unreadiness of people to countenance the necessary measures” for dealing with global warming, and that since democracy is a form of state power “it cannot be applicable on a global scale” (p.2). Holden then proceeds to demolish all three of these arguments and ends by offering a rather understated, yet optimistic, defence of democracy. His book largely went under the radar, receiving virtually no public attention and relatively little academic interest.

A few years later—and in the middle of this period of ‘suspended hope’ in the outcome of international climate diplomacy—these same questions were addressed in more polemical fashion by two Australian scientists, who came at them from a very different standpoint. I have therefore selected this book, David Shearman and Joseph Smith’s ‘The Climate Change Challenge and the Failure of Democracy’, as my 2007 Climate Book of the Year. I make this selection not because I think this book was particularly influential—although it was cited in the academic literature much more widely than was Holden’s book, and still is today.[2] Nor do I select it because I think their argument is particularly well-made. Rather, the importance of the book is in its timing and symbolism. It gave voice at an important moment in climate politics to a particular strand of thinking within environmentalism—namely, that stopping climate change is a more desirable public good than is preventing the replacement of democracy with more authoritarian and less representative forms of governance.

Reviewing this work from the mid-2020s suggests that it is even more important today than it was in 2007 to have a view on the questions raised by Shearman and Smith.

Who are the authors? David Shearman (b.1938) is emeritus professor of medicine, specialising in gastroenterology, at the University of Adelaide, following previous senior positions held at Edinburgh and Yale Universities. He co-founded the non-profit organisation Doctors for the Environment Australia (DEA) in 2002 and was awarded the Order of Australia Medal (AM) for services to medicine and to climate change. His junior co-author was Joseph Smith, with Philosophy PhD, is a research scholar in the School of Law, and also the Department of General Practice, at the University of Adelaide, and writer of several books on medical practice.

Shearman and Smith’s argument in the book is as follows. Facing the challenges of a changing climate of its own making, liberal democracy, because of its well-known flaws, is doomed to failure. “Liberal democracy, considered sacrosanct in modern societies”, they write, “is an impediment to finding ecologically sustainable solutions for the planet” (p.xi). As a system of government it is unable to make decisions that could provide a sustainable society. In response to such failure—and because of the unavoidable need to deal with climate change through state-sanctioned policies—more authoritarian forms of power will inevitably come to the fore. In adopting this position they “share Plato’s conclusion that democracy is inherently contradictory and leads naturally to authoritarianism” (p.xvi).

None of the forms of ‘strong government’ that the authors see in history, or in the present, are ones that appeal to them—the Roman Catholic Church, the feudal system, communism, a Singaporean form of democracy. And so, again following Plato, their preferred system of government to deal with climate change is a form of technocracy, with wise philosophers—i.e., the “eco-elites” (p.141), aka scientists, “the new elite warrior leadership” (p.xvi)—in control. In their words, “We argue that the [climate] crisis can best be countered by developing authoritarian government using some of the fabric of these [old or] existing structures”, and then describing the education and values of the new leaders who will battle for the future of the earth (p.xvi).

As some of the above quotes indicate, Shearman and Smith’s argument is an expansive one, although their historical analogies of ‘strong government’ are rather limiting. They engage with political theory through the lens of Plato and the deep ecology tradition, which results in a narrowly drawn perspective. (They are medical scientists, not political philosophers).

It is hard to see how Shearman and Smith escape the dilemma they outline—the inevitable failure of democracy, and the need for strong state-sanctioned policies to deal with climate change. For this reason their position seems to oscillate. They can boldly advocate for “a form of governance by authoritarianism abhorrent to liberal thinkers” (p.131) and that there is “merit in the idea of a ruling elite class of philosopher kings” (p.141).

At other times, however, they seem to retreat from this advocacy and seek out a ‘third way’ in between democracy and authoritarianism, what they call a “reformed democracy” (Chapter 10). This would be guided by the principles of a liberal university education—their “Real University” which will “provide the technocratic leaders of the future” (p.166)—the reform of legal systems, a reclamation of the commons, and what they acknowledge would be “a painful” commitment to “degrowth”. Yet their reformed democracy is one without the liberalism and autonomy of the European tradition of liberal democracies.

Shearman and Smith’s book was published in 2007 and since then the limitations of democratic forms of government for tackling climate change have had much great airing than previously. For example, just a few years later, and following the unsuccessful efforts at COP15 in 2009 to negotiate a stronger international climate treaty, the veteran science polymath and public influencer Jim Lovelock—whose 2006 book ‘The Revenge of Gaia’ I reviewed last month—put forward his faith in eco-authoritarianism. In a 2010 interview for The Guardian newspaper, Lovelock said that “Climate change is so severe”, that “it may be necessary to put democracy on hold for a while”.[3]

In the intervening 18 years since the book’s publication there has been a steady trickle of books countering Lovelock’s proposition, many of which adopt the same language used by Shearman and Smith, namely that climate change presents a “challenge” or a “crisis” for democracy. For example, Nico Stehr has recently published ‘The World We Have Created: Climate, Democracy and Knowledge’, which counters the Lovelockian argument that “political action based on the principles of democratic governance should be abandoned in favour of a more authoritarian approach.”[4]

In recent years, authors such as Mike Fiorino, Beth Edmondson and Stuart Levy, and Jon Naustdalslid have all written in defence of democracy as it confronts the challenges of climate change.[5] So too have Rebecca Willis and Amanda Machin, although their remedy for the democratic sclerosis exposed by climate change is much more radical than Shearman and Smith’s “reformed democracy”. Their analysis argues that the problem with democracy as a system for dealing with climate change is, to quote Willis, a problem “not of too much democracy, but of too little”. Both Willis’ and Machin’s visions are for much greater public participation and deliberation, not less, and is far removed from Shearman and Smith’s ‘third way’ and its “ruling elite class of philosopher kings” (p.141).

In the Preface to ‘The Climate Change Challenge and the Failure of Democracy’, Shearman includes a personal message directed, it seems, at his anticipated readers in the United States. He voices the “bitter disappointment” in American leadership that, he says, is felt by many, and laments that the model of “freedom but with diminishing collective responsibility” that he sees US democracy now offering, “is not [one] that can sustain the world” (p.xvii). Although their book warns that some form of authoritarianism may be inevitable, Shearman’s final appeal is that “democracy must be reformed”.

In some ways, Shearman and Smith’s 2007 book foreshadowed much subsequent writing on the question of climate change and democracy. Most of this subsequent literature, while recognising that climate change presents a “challenge” for democracy, argues that it is a challenge that should be met by reform of various kinds and not by abandonment to authoritarian forms of government.

© Mike Hulme, January 2026

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Other significant books published in 2007

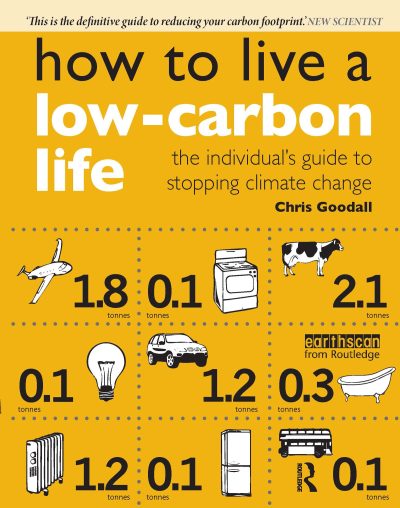

Goodall,C. (2007) How to Live a Low-Carbon Life: The Individual’s Guide to Stopping Climate Change. London: Earthscan. 319pp.

A new genre of books about climate change began to appear in the early years of the present century. These were what I will call ‘how-to’ books. They were clearly targeted at a new emerging audience of climate change readers, namely those who were wanting to find out either what they should do to avert a climate crisis, or else to learn what others ought to do, or could do, to minimize the risks of changing climate. The first of these ‘how-to’ books in relation to climate change that I have been able to locate in the English language was George Monbiot’s ‘Heat: How to Stop the Planet Burning’ (2006, Allen Lane). Not far behind him, however, was Chris Goodall’s book in 2007 ‘How to Live a Low-Carbon Life: The Individual’s Guide to Stopping Climate Change’, from the publishing imprint Earthscan, founded in 1982.

Whereas Monbiot’s book offered an expansive assessment of actions that could be taken to reduce emissions, Goodall focused very much on the practical decisions and life-style changes that individuals, particularly UK individuals, might take. The advertising blurb for the book framed his approach in no uncertain terms: “Drastic reduction of carbon emissions is vital if we are to avoid a catastrophe that devastates large parts of the world. Governments and businesses have been slow to act and individuals now need to take the lead. Western consumer lifestyles leave each of us responsible for over 12 tonnes of carbon dioxide a year—four times what the Earth can handle. Individual action is essential if we want to avoid climate chaos.”

Goodall offers a startingly individualistic approach to dealing with the problem of climate change. He seemed to have no faith in the possibility of supply-side changes in the energy mix and to have given up on governments, institutions or industry effecting meaningful change. Each of his chapters deals with a different aspect of an individual’s carbon footprint—home heating, lighting, household appliances, food, travel, and so on. Not all of the book’s recommendations have worn well. For example, his recommendation that if you need a new car you should buy a small manual diesel car failed to account for the adverse health outcomes of diesel emissions nor foresaw the rise of the electric car.

Since Monbiot’s and Goodall’s books appeared in 2006/07, these types of ‘how to’ books have greatly proliferated, with on average about two per year appearing in the English language. These ‘how-to’ books are intended to appeal very directly to prospective readers, in effect telling how, in a climate changing world, to variously ‘survive’, ‘keep cool, ‘prepare’, ‘think’, ‘speak’, ‘care for’, ‘act’, ‘manage’, or ‘live’.

Northcott,M.S. (2007) A Moral Climate: The Ethics of Global Warming. London: Dartman, Longman and Todd. 336pp.

The range of voices, disciplines and perspectives on climate change continued to diversify as the 2000s decade progressed. The growing volume of books about the changing climate and its challenges were no longer the preserve of scientists, economists, geographers, political scientists or even novelists and literary scholars. Philosophers and theologians now also began to take a serious interest in the ethical, moral and justice questions and dilemmas raised.

One or two books on climate change ethics or on climate justice had begun to appear earlier in the decade, but Michael Northcott’s 2007 book ‘A Moral Climate: The Ethics of Global Warming’ was, I think, the first in the English language to deal at length with climate change ethics written by a theologian. Northcott was a trained theologian, a professor of ethics at Edinburgh University, and a practising priest in the Scottish Episcopal Church. Other theologians were to follow this example in the years to come, including two more by Northcott himself.[6] The Foreword to the book, a form of blessing from a fellow Christian, was written by the 76-year old Sir John Houghton, the former Co-Chair of the IPCC’s Scientific Working Group.

I bought my own copy of ‘A Moral Climate’ in September 2007, shortly after it was published, and wrote a short review of it at the time for the Christian monthly magazine Third Way (now discontinued).[7] At the time I described the book as “hard-hitting”, written as “a polemic against the evils of neoliberal capitalism”, with Northcott standing in the line of Biblical Old Testament prophets—such as Jeremiah, whom Northcott widely cites.

But my review was critical of Northcott’s reliance on climate science for reaching the moral conclusions he did. I also called out his strain of what, a few years later, I would call ‘climate reductionism’. I wrote that “blaming climate change for everything that’s wrong with the world and … for everything that will be wrong in the future world is too neat a formula”. Nevertheless, the book is significant for the passion with which Northcott argues that climate change presents a specific moral challenge to human beings.

[1] Holden,B. (2002) Democracy and Global Warming. London: Bloomsbury/Continuum. 194pp.

[2] Shearman and Smith’s book has been cited 529 times in the past 18 years, in contract to Holden’s 117 citations over 23 years, nearly six times higher a citation rate. (Source: Google Scholar).

[3] Hickman,L. (2010) James Lovelock: Humans are too stupid to prevent climate change. The Guardian newspaper, 29 March. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2010/mar/29/james-lovelock-climate-change

[4] Stehr,N. (2026) The World We Have Created: Climate, Democracy and Knowledge. New York: Routledge.

[5] Machin,A. (2013) Negotiating Climate Change: Radical Democracy and the Illusion of Consensus. London: Zed Books; Fiorino,D.J. (2018) Can Democracy Handle Climate Change? Cambridge: Polity; Willis,R. (2020) Too Hot to Handle? The Democratic Challenge of Climate Change. Bristol: Bristol University Press; Edmondson,B. and Levy,S. (2013) Climate Change and Order: The End of Prosperity and Democracy. London: Palgrave MacMillan; Naustdalslid,J. (2023) The Climate Threat. Crisis for Democracy? Cham, Switzerland: SpringerNature.

[6] Northcott,M. and Scott,P.M. (eds.) (2014) Systematic Theology and Climate Change: Ecumenical Perspectives. London/New York: Routledge; Northcott,M. (2013) A Political Theology of Climate Change. Grand Rapids, MI/London: William B Eerdmans/SPCK.

[7] Hulme,M. (2007) Review of ‘A Moral Climate: The Ethics of Global Warming’. Third Way, December 2007, p.6.